…contained in the assumption of neutral, impersonal writing styles is the lack of risk…we have lost the courage and the vocabulary to describe [the personal] in the face of the enormous social pressure to “keep it to ourselves”—but this is where our most idealistic and our deadliest politics are lodged, and are revealed.

—Patricia Williams, The Alchemy of Race and Rights

Writing instruction is a political process.

—Julie Lindquist, “Class Affects, Class Affectations: Working Through the Paradoxes of Strategic Empathy”

These encounters with high school students and misses with support staff take place within the framework of a first-semester writing seminar. And so it seems appropriate to turn now to the deeply classed nature of writing itself, both pronounced and obscured by entry into an institution and a course where learning academic writing is paramount.

My goals as a writing teacher hover and tangle: To teach the skills of conventional academic writing, what literacy educator Lisa Delpit calls “codes of power,” to students who are diverse by class.Lisa Delpit, “The Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People’s Children,” Harvard Educational Review 58, no. 3 (1988): 163. And to help students learn to write in ways that take on conventional structures of language and power, becoming a source of power that can speak to power. And to open the space for those students to add their voices to the discourse, by taking up alternate forms of literate expression and offering us rich windows on different ways of being and communicating.Patricia A. Sullivan, “Composing Culture: A Place for the Personal,” College English 66 (2003): 46.

Teaching college writing sits right at the hub of language, class, and power. As literacy theorists recognize, some students arrive still needing to learn conventions they’ll be expected to perform throughout college, while others are already prepared to play with those forms. Delpit argues for the importance of explicitly teaching “codes or rules…for participating in the culture of power” to those who have less power, not to dismiss home languages but to amplify students’ options.Delpit, “The Silenced Dialogue,” 163.5 David Bartholomae also notes the value of teaching students various forms of expression, including but not limited to discourses of power. He offers Patricia Williams’ Alchemy of Race and Rights—a compellingly unconventional text from which we read in this final section of our course—as a text in which the “writing is disunified; it mixes genres; it willfully forgets the distinction between formal and colloquial, public and private; it makes unseemly comparisons.…features we associate with basic writing, although here those features mark her achievement as a writer, not her failure.”David Bartholomae, “The Tidy House: Basic Writing in the American Curriculum,” Journal of Basic Writing 12, no. 1 (1993): 11. How do writers show that they know they are playing with convention, and why does this matter?

Even listing these goals and questions reveals a split: Academic writing—a code of power—is conceptualized as distanced, impersonal, abstract, not as narrative or concrete. How to nurture a weave, a richer, more full-bodied set of possibilities? Understanding that “class is experienced in terms of affect, nostalgia, and desire,” composition teacher Julie Lindquist coaches her working-class students in “narrative theorizing that enables consciousness of the particulars of class experience.”Julie Lindquist, “Class Affects, Classroom Affectations: Working through the Paradoxes of Strategic Empathy,” College English 67 (2004): 189, 194. In this mix, class can operate as a source of power, integral to how and why people tell their stories.

Literary critic Barbara Christian also insists that “narrative” can be a form of theorizing. Focusing on differences of race more explicitly than of class, she clarifies how splitting stories from ideas, academic from personal, is a political act, and how refusing this split carries its own clout:

People of color have always theorized—but in forms quite different from the Western form of abstract logic…our theorizing…is often in narrative forms…in the play with language, since dynamic rather than fixed ideas seem more to our liking…the women I grew up around continuously speculated about the nature of life through pithy language that unmasked the power relations of their world.Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory,” Cultural Critique: The Nature and Context of Minority Discourse 6 (1987): 52.

Lindquist and Christian suggest that narrative can be theory, that telling stories can help create critical spaces for reconsidering the locus and purpose of writing. Teaching writing can tease out nuanced, contradictory experiences of class, where stories and speculations, in all of their “variety, multiplicity, eroticism,” are powerful, sometimes “difficult to control.”Christian, “The Race for Theory,” 59. Telling stories can intervene in structures of power.

On the first of December, Anne’s daughter Marian, an urban farmer and educator, comes to talk with our classes about a “class autobiography” she’d written a few years earlier, when she herself was in college. Marian’s ‘zine, “For what(ever) It’$ Worth: Reflections, thoughts, and suggestions on Class Privilege, Inheritance, and Inequity from a young white woman of wealth,” is a frank interrogation of what it means to inherit a lot of money. Anne introduces her daughter: Mar and I are both taking a pretty big risk today—she to come as a guest speaker and facilitator to her mother’s (!) classroom, me to come out to you all as the mother of a millionaire—and then we move into a silent discussion about class: moving around our classroom and commenting anonymously on large posted sheets with questions about key words—home, work, clothing, health, space, recreation, income, education. After we discuss this, Marian talks about writing her ‘zine, which infuses identity work with political analysis. Owning her membership in the “owning” class counters the debilitating “narcissism” of guilt and opens up her work in the world, as she asks, “What can I do with having money?”Marian (Paia) Dalke, “For what(ever) It’$ Worth: Reflections, thoughts, and suggestions on Class Privilege, Inheritance, and Inequity from a young white woman of wealth,” self published, January 2009.

Students are intrigued by what Marian has to say, and curious, though uncertain, about the alternative ways she chooses to say it:

What’s happening in the space opened up by the clarity—

paradoxically “messy” and “unperfected” in its texturing of struggle—of Marian’s ’zine?

In acknowledging that “people are poor, in part, because of the concentrated wealth that I have benefited from,” Marian opens the door to a personal way of going beyond the personal, a form of “narrative theorizing” from a position of power. Her ‘zine reorients our gaze, suggests how varied forms of writing might help unsettle our investment in classed ways of distinguishing ourselves.

Both to continue this unsettling and help our students imagine alternatives, we unbind our next assignment from conventions they’ve been working all semester to master:

By 5 p.m. Friday (Dec. 9):

writing assignment # 11, 3 pp. (or equivalent) “de-classifying” your writing for this class, going beyond the weekly 3-pp. papers you’ve been writing for Jody and Anne. What would you like to say to the whole Bryn Mawr community—or to the whole world??—about issues of class and education? What new format might you play with, to say these things? (Marian’s zine may have given you some ideas… .)

Not surprisingly, the confidence with which students take up these options is inflected by class.

We hear quickly from Chandrea:

I was discussing my confusion on the next assignment we have to do for this class…, and my cluelessness reminded me of how dependent I am on writing academic papers. I remembered worrying, “What do you mean it doesn’t have to be in the form of an academic paper?!”…I’m so used to writing papers in this class as well as other classes…That’s all we did in high school! I mean, I could do a poster or something but I really am not that creative/artistic as I’d like to be. Maybe a slam poetry presentation would work for me because I think those kinds of things are fun… . I never expected to come to college and be told to do anything but write papers when it came to expressing my ideas…Chandrea, “Different Forms of Expression?” December 3, 2011 (4:56 p.m.).

Several days later, she returns to our public forum:

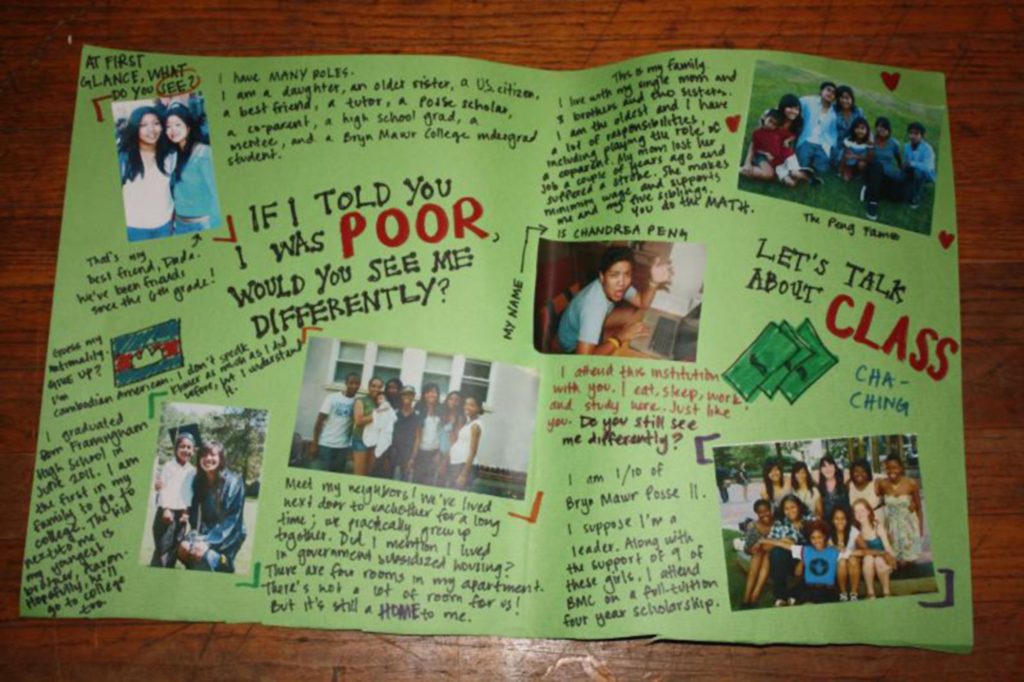

This is a poster-collage that I did last night. I was pleased yet frightened with the finished project and I ended up running to my posse. They were really proud of me and wanted to do their own version of the poster-collage. I was inspired by Marian’s zine and I remember being so amused with it because I could relate on so many levels – except that instead of being a millionaire, I decided to declare that I was FAR from that. I think I’ve always kept my socioeconomic status as a secret in high school and now that I’m in college, I’m deciding to own up to my status, just like Marian did. I’m actually thinking of posting it outside of my dorm because I don’t know what else to do with it. But I don’t know how the people on my hall will react or if they will react at all. I kept the class workshop in mind because we discussed broadening the audience when it came to talking about class. And my audience is the Bryn Mawr community as a whole.

On the bottom left, next to the picture of me and my little brother it says: “I graduated from Framingham High School in June 2011. I am the first in my family to go to college. The kid next to me is my youngest brother, Aaron. Hopefully, he’ll go to college too.”Chandrea, “If I told you I was poor, would you see me differently?” December 9, 2011 (5:34 p.m.).

Chandrea’s poster plays with genre to invite and challenge viewers to examine our assumptions about who she is, and who we are. Her turn here from the conventions of schooled writing, revealing herself in relation to material goods, family, and friends, engages her in a creative act that maps her capacity to be in more than one place at the same time.Walkerdine, “Using the Work,” 760.

Chandrea writes herself “poor.” Another student, “Hummingbird,” also struggles toward a more complex cartography, in which she gets written as “privileged.” Her final project for the class, which opens with a letter, is called “Classism v. Feminism and Why a Discussion about MTV Can Get Very Complicated Very Fast.” It is set in a college dining hall, where a disproportionate share of working class students work alongside regular college employees.

Dear Bryn Mawr College Dining Services,

You are all amazing people. To run this dining hall is like running the world. To deal with these dumb whiny bitches is too much! If they are trying to take the television out of the dining hall b/c they say that too many of the music videos objectify women, then they have meaningless and idiotic lives. You shouldn’t take the dumbass bullshit from these privileged students. If they feel as though they are being objectified, they should write to MTV who shows the videos and, most importantly, the artists who produce the music. To complain about music videos and a television?! Most of the women, girls really, who complain, don’t respect the spaces that they live in. They have no reason to complain about this place. Don’t take the TV away. Rather, tell the snooty dumbasses to SHUT THE FUCK UP! YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT REAL OBJECTIFICATION IS!!!

Sincerely,

POSSE SCHOLAR

Confused? I was too.

Actually, my range of emotions went from bewildered to outrage to confusion to (perhaps?) understanding and finally frustration. But this story didn’t start out being about class.

A few weeks ago Bryn Mawr College screened MissRepresentation. The documentary explores the ways women have been poorly portrayed by the media. My hallmates felt empowered by the film. My friend, Nina*, thought of the television in the back of Erdman dining hall and how the only channel is MTVu (the University/College version of MTV). She commented on the way the majority of the programming objectifies women. Nina contacted Dining Services to see about having the TV removed. Dining Services said Nina would have to get a petition signed, as they didn’t have the full authority to act on a request like hers.

Soon afterwards, two petition sheets were posted and I signed the one that read “I do NOT think MTVu improves my dining experience.” As we were leaving, we took a look at the napkin notes and realized a debate was occurring.

Napkin Notes are a Bryn Mawr Dining Hall institution – pinned to a bulletin board for the dining staff to read. Students can request grapes at lunch, for example, thank Dining Services for a job well done. The MTVu conversation changed the Napkin Notes Board, though, because they were a conversation between students. When I first saw them, only two had been put up, both expressing a preference for ending the MTVu service. Nina and I were excited that napkin notes were being used to host a discussion. I wrote my own note to post on the board:

“I don’t want MTVu in the Dining Halls, because I don’t want to see degrading images of women while eating breakfast. We should be feeling empowered, not overdressed.”

I felt good after adding my own voice. My friends agreed with my sentiment and commended me for writing. And then, a few days later, I saw the note we started with.

I was shocked and felt the accusations that those of us who disagreed with the presence of the TV were “privileged” were unfair and unfounded. I was also struck by how this conversation very suddenly became about class and not about gender. We had been labeled “snooty bitches” and we “[didn’t] know what real objectification [was].” After the shock subsided, I was outraged. How dare she accuse me of being privileged because I didn’t want to have to watch degrading images of women, in a women’s college? Another note written in response to the angry note asked what gave her the right to conflate privilege with the ability to point out objectification. Then I reread the first note and noticed she’d identified herself as a Posse Scholar.

Posse scholars get a special scholarship based on their leadership skills. Scholars meet on a regular basis throughout their senior year of high school to discuss a range of subjects, including race, gender, and class, and they seem to be some of the most socially aware students.

I decided to talk to my hallmate, another Posse Scholar… . To my surprise, she said she could understand both sides of the story. She explained that when she was growing up she watched MTV all the time. She could understand seeing a level of privilege in those who didn’t watch MTV growing up. I was skeptical at first, but then thought about it. Could there be a classed difference in whether or not one grew up watching scantily clad women fawn over rappers? My hallmate also suggested the Scholar assumed our notes were directed to the staff—who work hard enough as is—instead of towards each other.

So I’d come to (almost) understand the student’s strong response. But if watching MTV as a child was, indeed, a sign of class difference, why did degrading women have to be a part of that? Every day, I felt as though I was being reminded that my job as a woman (or girl) was to be seen and not heard.

I understand that removing a television won’t stop MTV from showing videos that objectify women. I also understand that not everyone has the option to not view this objectifying media. However, I do think removing a TV which is currently owned by the MTV corporation is taking a step.

*Name has been changed. Names on the Napkin Notes have been erased for anonymity.Hummingbird, “Classism v. Feminism and Why a Discussion about MTV Can Get Very Complicated Very Fast,” December 9, 2011 (6:46 p.m.).

Hummingbird’s account traces her recognition of how different backgrounds can lead to different perspectives, and suggests how complex and fraught it is to navigate toward new understandings and actions. While Pratt’s “literate arts of the contact zone,” which we discussed early in the semester, feature the reach and risk of those on the lower end of power relations, Hummingbird’s communication—also reaching, risking—invokes another source and purpose.

The way Hummingbird participates in the shared spaces of napkin notes and on-line dialogue suggests a confidence with putting forth her voice that may also be classed. She recognizes this as she reflects on her process: feeling “good after adding my own voice”; realizing that she’s one of the “snooty bitches” being called out by a Posse Scholar who is likely “socially aware”; then asking, “Could there be a classed difference in whether or not one grew up watching scantily clad women fawn over rappers?” On the other hand, her queries throughout the piece use the middle-class convention of framing questions rather than making assertions; as Delpit notes, such oblique communication can betray discomfort with the power one holds.Delpit, “The Silenced Dialogue,” 284.

In this early moment in her college experience, Hummingbird tries to write herself into understanding another upbringing. Both off-line and on,Comments, “Classism v. Feminism and Why a Discussion about MTV Can Get Very Complicated Very Fast,” December 10, 2011 (2:39 a.m.)—February 2, 2012 (7:36 p.m.).8 her writing generates a hot dialogue that includes “rage, incomprehension, and pain…wonder and revelation, mutual understanding, and new wisdom—the joys of the contact zone.”Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” 39. Hummingbird continues to struggle publicly, and to shift position:

Last Friday (December 9th) I posted an opinion piece on the napkin notes and MTVu discussion… . When I wrote it, I knew it would be public—that was part of the assignment for our class. However, I didn’t realize how quickly it would spread to be a topic of discussion. Even as we speak the MTVu situation is growing more and more complicated… . I no longer feel confident that removing the TV is our best option… . I think the school’s best option right now is to host more discussions like the ones I’ve had with my friends—discussions which focus on sharing our experiences and thoughts on all these intersecting topics: gender, race, and class. Bryn Mawr is not a homogenous group and I think pushing on these tense topics can only help the student body and college grow as a whole.Hummingbird, “Gender, Body Images, and (M)TV,”

December 16, 2011 (12:25 p.m.).

As Anne and I had done with the high school partnership and on-campus workshop, Hummingbird turns to dialogue as a way to generate learning and “growth.”

From their differently classed positions, Chandrea and Hummingbird engage in narrative theorizing, calling on their experiences in transition to put forth risky thinking—not just to their teachers but to an audience that is both closer—in the dormitories where they live—and larger—on the internet. In her description of a “contact zone,” Pratt notes that “one had to work in the knowledge that whatever one said was going to be systematically received in radically heterogeneous ways that we were neither able nor entitled to prescribe,” and calls for “a systematic approach to the all-important concept of cultural mediation.”Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” 39, 40. Chandrea and Hummingbird occupy a contact zone, both in class and out of it, where their words shift meaning once exposed to others. I here lay their stories alongside one another, reading them as linked and mutually echoing, gestures toward futures that might surprise.

JHarmon

JHarmon Michaela

Michaela Chandrea

Chandrea Hummingbird

Hummingbird