This cluster of classes takes me to some of the hardest, most unanswerable and vulnerable places I know; pushes hard against my capacity to understand others and self; leaks into my pedagogy, leaving me with a rawness, a deep uncertainty about what it means to teach and learn in such circumstances. My co-teachers and many of our students articulate such feelings. When we enter the prison, we encounter an extreme edge: the vulnerability, sometimes trauma of the people inside; a visceral encounter with the social, political trauma of mass incarceration. As I hear from students, this triggers a reencounter with self: How/can I stay, listen? What can I understand, or not, how can I respond? Some look not only to us but also to each other with these questions. Authority seeps, circulates.

While the jail “triggers,” brings our shared vulnerability to the fore, rendering it intensive, defining, we also bring our own hauntings, relationality, mortality. So it is that in the midst of the semester I undergo a psychic and physical wounding as I am diagnosed with a small but fast-moving breast cancer. Within weeks I undergo a minor surgery that heals and also wounds, leaving me with a scar and disturbing questions. Exiting the clinic, I walk 11th Street strung up with awareness of the ultimate vulnerability “that emerges with life itself,” “precedes the formation of ‘I’”Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (Brooklyn: Verso, 2006), 310.—and attends our exit from living. This precarity strangely anchors me in a remembrance of all we don’t know of one another as we pass on the street. Heightening the visibility of circumstances of radical vulnerability can carry peril, elation, potentiality.

When Anne reads the trauma novel Eva’s Man with our students, one arranges an alternative assignment, trashes the book in their dorm room, then removes it utterly from their space; others say they struggle with being a “traumatized scholar” in the classroom; a third is “so glad I read this book, it changed my life.”

We are in our 60s, some of our students not yet 20. It is astounding to be working together, figuring our way through precarity.

Roger Simon and Claudia Eppert share a framework they’ve developed working with students who bear witness to trauma: witnesses must listen, remember what they hear, recognize its importance; acknowledge that although they are outsiders to this experience, these “memories of violence and injustice press down on [their] sense of humanity.” And they must take action: carry the stories they’ve heard into other contexts, retelling narratives as a way to exert agency and provoke protest to injustice.Roger I. Simon and Claudia Eppert, “Remembering Obligation: Pedagogy and the Witnessing of Testimony of Historical Trauma,” Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de l’éducation 22, no. 2 (Spring 1997): 178. In this framework, witnesses are not just repositories but also actors, with an invitation—or an obligation—to bring what they have learned to bear on others, to make an impact. For our students, and for us, this is oddly inclusive, offers us a position of strength, of some efficacy.

In line with this call, my co-teachers and I are now asking our students to find ways of communicating publicly what they are learning from our prison work. Initially, our students resist: like us, they are often unsure about what they are doing in the prison. Early on, we invite in a creative consultant who has long made art that renders the Prison Industrial Complex visible to those outside it. She proposes that our students use the writings of women inside as the central texts for their public project, but they push back hard on what seems to them a self-interested, even dishonest agenda: soliciting and exhibiting others’ lives for still others to view feels antithetical to what they are trying to do: build trust and mutuality, as they lead a reading and writing group. And so begins a variegated dance of fits and starts as the students resist and engage in research and expression. Right up to the day of the exhibit, in the most central and public space on campus, many of us vocalize uncertainty about whether this will come off, what it will look like.

As several of the students explain, they are struggling to recognize the trauma of mass incarceration in the “forced vulnerability” of those who are incarcerated, in the dehumanization of enforcers, and in their own involvement:

As Simon and Eppert gloss this experience: absorbing “something absolutely foreign…may call into question what and how one knows” and so bring oneself to the edge.Simon and Eppert, “Remembering Obligation,” 180.

Leaving their sense of themselves as knowers behind as they immerse themselves in a shared humanity with those who are incarcerated may be particularly jarring in light of the charge to know, to achieve, even to make a difference. And yet it is from these questions and this edge that our students act: move hesitantly, resistingly to share their learning.

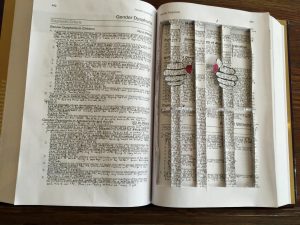

Their exhibit is astonishing. “Freedom Forgotten: Works of Silence and Resistance” sets forth words, images, and actions of incarceration earlier and now, of Asians, American Indians, Black, Latinos, white people. And draws others on campus into consideration of how identities and locations create one another: an empty hoodie floats over pastoral calm; a carved book insinuates words by incarcerated transgendered people between the lines of the DSM-V, where “gender dysphoria” is newly offered as a diagnosis; a sculptured torso is pierced with wire and etched in words and prisoner ID number; text magnified from the minutes of the Student Governance Association exposes racial issues on campus, in counterpoint to images and words that have excluded American Indians, via both education and criminalization.“Freedom Forgotten: Works of Silence and Resistance (Some Photos and Commentary),” December 13, 2015 (7:51 a.m.).

In the hours of mounting the exhibit, and in the days of its visibility, skeins stretch between college and prison: invite into consciousness the hauntings of these apparently separate institutions; and in this way gesture—in what students later describe as a “flash mob exhibit,” “less exhibit than invasion in the lives of people at college,” “a labor of love”—welcoming ghosts.Tuck and Rhee, “Glossary,” 654. Later too, students say, Now I have to open up this conversation in my [Chinese/Indian American/conservative] community. The work we do at home has deep emotional ties, I don’t know yet how to do this. We glimpse our own and others’ frightening tenderness, throw up protective gear, pierce the skin, and etch ink over and through our scars. Students leave, show up again, for now: Stakes are high.

In our final meetings with our students and their last written reflections about classes, both in jail and on campus, they speak of their own processes, where they will go with this work. Four will return to work in the jail next semester, the decision of one especially surprising, given her report of trauma and even paralysis. Several say they will not return—this work is too painful and without clear enough benefit. No one says it was easy. And some of it is very hard to listen to: it can be painful, discordant to hear students’ vulnerabilities inside the larger networks of our shared precarity. A few struggle with whether this experience was too difficult, hindered their learning. We talk with each other about our own struggles: the receptivity and investment, the releasing and reengaging of authority that this kind of teaching has asked of us.

Still, one of our students writes of the day things fell apart inside: “This was the experience that stood out to me, this was the experience that I will take with me in anything I do after this 360, not just in abolition and prison work, but in my life as an individual, made up of all of the experiences and people and words and lessons and moments I have ever been part of.”Joie Rose, “The Last One (Prison Reflection),” December 15, 2015 (7:45 p.m.).