If we refuse to become women, what happens to feminism?

—Judith Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure

During the 1900-01 academic year, a student using the initials E.T.D. published a short story in Bryn Mawr College’s bi-weekly magazine, the Fortnightly Philistine. Entitled “The Crime,” the narrative focuses on the experiences of a second-semester senior struggling unsuccessfully with the stresses and pressures of academic life. Apprehensive about the concluding assessments of her college career, she comes to embody such a state of fearful extremity that she is unable to complete her work. Although she proclaims that “I am in perfect possession of my senses. Nervous, yes; very nervous, very melancholy but not mad, no, no!,” the story ends when “the unfortunate Senior, who had been an exceptionally good student…dashed her head against the corner of the table and expired, raving mad.”E. T. D.,“The Crime,” 7 (February 1, 1901): 2–4, Internet Archive: Bryn Mawr College Library, Special Collections.

We open our project with this story because it so acutely dramatizes our central theme: the dynamic relationship between intellectual achievement and mental disability. “The Crime,” which riffs on Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” is explicit in its portrayal of a young woman’s mind under pressure, so fearful of her inability to meet Bryn Mawr’s standards of academic accomplishment that she eventually does violence to herself. We use the term “disabling achievement” to name this nexus of anxiety surrounding intellectual performance: it is our description of the mechanisms whereby aiming for achievement can have the “crosswise,” or “transverse,” effect of generating disablement. Because we believe that insistent emphasis on advancement, progress, and futurity—as well as institutional focus on preparing students to meet these demands—disables us all, we begin to craft here a space in which the structures of cultural achievement need not disable. We re-envision an institution in which no one need gain intellectually at the cost either of her own mental health, or of another’s loss or failure. We end with a particular focus on the disabling quality of those time-pressures that structure, animate, and strangle academic life. Throughout, we traverse the tensions between institutionalizing disability studies and the field’s promise of destabilizing the constrictions of normativity.See also Sharon Snyder and David Mitchell, Cultural Locations of Disability (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 192.

The 100-year-old story of “The Crime” serves both as dramatic backdrop and historical scaffolding for the disabling dimensions of women’s higher education. The scene we set at our home institution extends into multiple larger, intersecting discourses of mental dis/ability, feminism, education, and queer studies. Fifteen years before “The Crime” was published, the founders of Bryn Mawr College had addressed head-on a particularly disabling understanding of “women’s nature.” Early proponents of the College were challenged by a contemporary belief about the distinctive frailness of female bodies, a view championed most ardently by Edward Clarke, a Harvard Medical School professor who began his study of Sex in Education; or, A Fair Chance for the Girls with a description of “closed bodily systems,” which contained “only finite amounts of energy”: For young developing women, studying pulled “blood, nourishment and energy away from reproductive organs that were in the fragile and critical stages of maturation.”Barbara Ward Grubb and Emily Houghton, “Building Muscles While Building Minds: Athletics and the Early Years of Women’s Education” (September–December 2005). Concerned that excessive study would divert a young woman’s finite energy supply from her reproductive capacities, inhibiting and threatening the health of generations to come, Clarke argued that only by avoiding college studies could a young woman “retain uninjured health and a future secure from neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria, and other derangements of the nervous system.”Edward Clarke, Sex in Education; or, A Fair Chance for the Girls (1873; repr., New York: Arno, 1972), 41–42.

The second president of Bryn Mawr, M. Carey Thomas, whose vision was definitive in shaping the College’s mission, spoke of being “haunted…by the clanging chains of that gloomy little specter, Dr. Edward H. Clarke’s Sex in education.”M. Carey Thomas, “Present Tendencies in Women’s College and University Education,” Educational Review 35 (January 1908): 69. In a 1908 address celebrating Bryn Mawr’s “experiment” of offering women rigorous intellectual engagement that would not adversely affect their minds or bodies, Thomas proclaimed that the

passionate desire of women of my generation for higher education was accompanied throughout its course by the awful doubt, felt by women themselves as well as by men, as to whether women as a sex were physically and mentally fit for it… . We were told that their brains were too light, their foreheads too small, their reasoning powers too defected, their emotions too easily worked upon to make good students. None of these things has proved true. Perhaps the most wonderful thing of all to have come true is the wholly unexpected, but altogether delightful, mental ability shown by women college students.Thomas, “Present Tendencies,” 64, 70.

Thomas countered Clarke’s description of women’s fragile biological structures by taking a stand against the social convention of intellectual isolation: young women, she claimed, had been “crushed by the American environment,” not “enabled by circumstances to use their powers” because they had been “cut off from essential association with other scholars.”Helen Horowitz, “Women and Higher Education: A Look in Two Directions,” Heritage and Hope: Women’s Education in a Global Context, talk at Bryn Mawr College (September 23, 2010).

Although Thomas imagined an intellectual community in which such isolation would be reduced, one of the ironic outcomes of her vision has been the current perpetuation of what we see as isolating academic practices.

It is our hope to intervene, here, in the disturbing dynamics set in motion by the scholarly ambition and attainments of women. We use E.T.D.’s story, in the context of Bryn Mawr’s founding, as paradigmatic of an ongoing, uneasy relationship between women’s education and mental health, as we attempt to further refigure the relationship among individuals and institutions, personal narratives and larger theoretical claims. Our project is thus an extension of Thomas’s, which took a stand against Clarke’s vision of the female body as a closed system, in order to explore the possibilities that might lie in more open networks.

Although expressed in different language, disquietude about “feeble minds” is as prevalent in the early twenty-first century as it was in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth. We no longer call unsettled minds “hysteric,” but describe them instead with a range of DSM diagnoses, including “anxiety,” “depression,” “bipolar disorder,” “OCD,” “anorexia,” and “bulimia.” In “Revisiting the Corpus of the Madwoman,” Elizabeth Donaldson argues that it is impossible to reconcile such “medical discourses of mental illness, which describe the symbolic failure of the self-determined individual,” with “the competing discourses of democratic citizenship, in which will and self are imagined as inviolable.”Elizabeth Donaldson, “Revisiting the Corpus of the Madwoman: Further Notes toward a Feminist Disability Studies Theory of Mental Illness,” in Feminist Disability Studies, ed. Kim Q. Hall (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 107.

The conflict Donaldson identifies between the individual and the communal, between medical diagnoses and their social implications, is also highlighted in our recent fundraising campaign, “Challenging Women: Investing in the Future of Bryn Mawr.” In its review of the contemporary challenges “which Bryn Mawr must be able to prepare its students to meet”—

to continue to advance as women in science; lead in the arts and humanities; prepare effectively for life in an increasingly global environment; build strong, diverse communities; use technology for teaching and learning; and strive for balance between academics and other aspects of a modern, healthy life“Challenging Women: Investing in the Future of Bryn Mawr,” Alumnae Bulletin, Bryn Mawr College, Spring 2003, italics added.

—the language of the campaign bears witness, particularly in this last clause, to the continued uneasy relationship between academic achievement and health.

This dynamic is beginning to garner attention in the field of disability studies. Several years ago, Catherine Kudlick wrote a short article challenging the “normative ideas” underlying our conceptions of “academic competence,” and questioning the “unhealthy forms of intellectual conformity” they entail. Catherine Kudlick, “A History Profession for Every Body,” Journal of Women’s History 18, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 164–65. Margaret Price’s 2011 Mad at School was the first book-length scholarly text, however, “to broaden the field of DS and…the field’s long-standing emphasis on sensory impairments,” by focusing on mental disability in the particular context of the academy.Margaret Price, Mad at School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), 5. Price argues that “academic discourse,” in its appreciation of rationality and reason, “operates not just to omit, but to abhor mental disability—to reject it, to stifle and expel it.”Price, Mad at School, 8. Drawing on her assessment of the ways in which educational institutions like Bryn Mawr continue to promote a profound distinction between intellectual work and mental disability, we suggest that they are instead dialectical, each constituting and negating the other.

Sharing both M. Carey Thomas’s commitment to the academic achievement of women, and E.T.D.’s fears about the costs such achievement entails, we attempt here to open up possibilities both for enabling women and “disabling,” or “undoing,” what the category of “achieving women” entails. In advocating for a more open and collective system, we both resist Edward Clarke’s closed one and welcome all forms of mental variety. In an era when the classification “woman” is under interrogation, and when women, however defined, can find their education at almost any academic institution, we suggest ways in which single-sex institutions like Bryn Mawr might better respond to the particularities of, as well as to the increasingly diverse and complex interactions within and among, their student bodies. From the particular location of feminist disability studies, we add to the ongoing deconstruction of “the unity of the category of woman” a range of questions about feminist valorizations of “individualistic autonomy.”Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, “Integrating Disability, Transforming Feminist Theory,” in Feminist Disability Studies, 16, 34.

Bryn Mawr students call themselves “Mawrtyrs,” as a punning expression both of their undying devotion to their academic work, and of the profound ethics of this allegiance. In this essay, we call for a shift from “mawrtyr-dom” to a more open-minded, open-hearted way of thinking about intellectual work. To signal that shift, we employ a polygeneric form of writing, juxtaposing personal narratives with theory drawn from disability and queer studies. Using all of these voices to probe and ponder the others, we portray a messier world than the one described in Bryn Mawr’s Alumnae Bulletin, one that replaces the binary constrictions of healthy and sick, sane and insane, with a more hybrid form: disarrayed, cluttered, toggling between disablement and enablement.

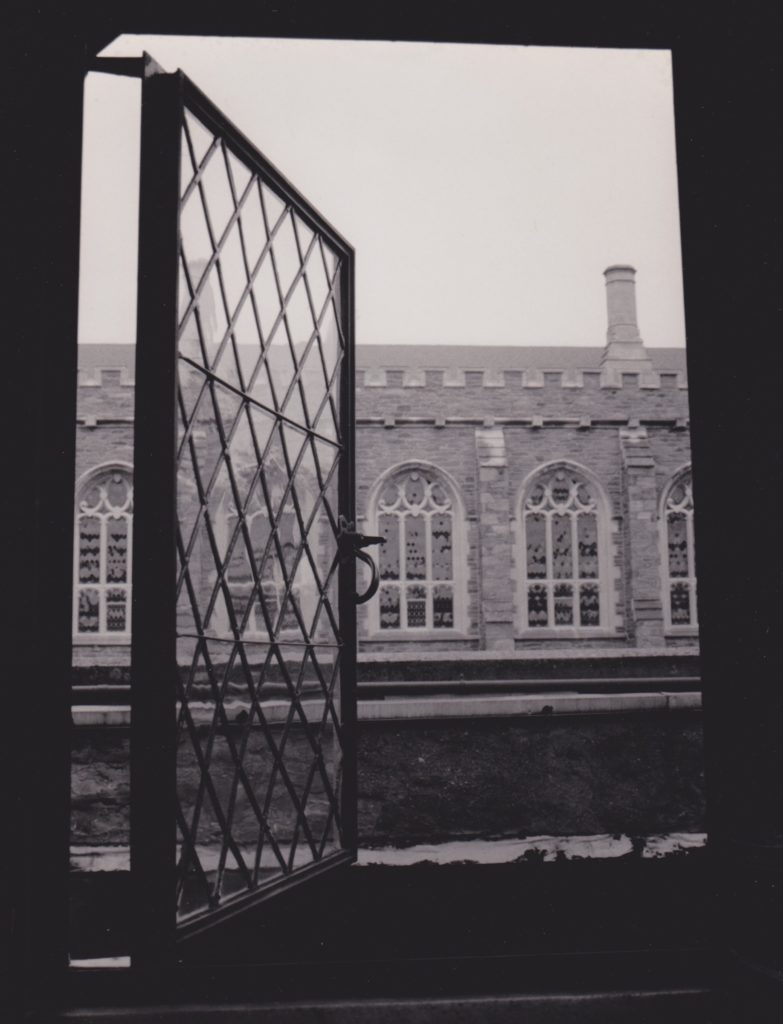

The protagonist of “The Crime,” unable to be a “complete master of herself,” fails to muster the characteristics needed to excel in a demanding academic environment. The leakiness and instability inherent in her madness, the “trickling, horrid drops” of ink that consume her “boiling brain,” stand in contrast to the “stolid” buildings of the College,E.T.D., “Crime,” 2–4. which represent the sharply defined demands of academia that she cannot meet. Her unsteady movement enacts a form of “maddening” that results in disaster. We advocate, here, another version of her “waffling” and “wobbling,” one with a different, and more socially useful, result. If we can resist “walling off” disability, we might prompt instead a form of interdependency defined by mutual vulnerability—and mutual desire.

In “The Crime,” the protagonist’s “horror of the appliances of study grew” until she had “a look of feverish intellectuality” that “no mere fleshly seeker of marks could rival.” “An exceptionally good student” is thus “maddened” by the intersection of the College’s demands with her own desires to achieve them.E.T.D., “Crime,” 3–4. Although her ostensible “crime” is that of stealing others’ ink (in order to forestall the dreaded final exam), her larger fault is her failure to meet the institution’s expectations of academic performance. Perhaps an even larger “crime”—etymologically: “fault,” or “cry of distress”Douglas Harper, “Crime,” Online Etymology Dictionary.—is that of the College, which places those rigorous demands on her. A hundred years later, the “mad pride” movement speaks to this dynamic by stressing the fruitful potential of mental variety and difference, and advocating, thereby, movement across presumed categories of disablement.