“You should be aware that failure is a distinct possibility.” That was so freeing.

–Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “The Hard Truths of Ta-Nehisi Coates”

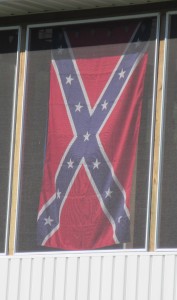

Yesterday, “Confederate flag wavers greeted President Obama in Oklahoma.”Arlette Saenz, “Confederate Flag Wavers Greeted President Obama in Oklahoma,” Good Morning America (July 16, 2015)

Today, as I take my usual morning walk—several miles looping out of the farm and back again—I, too, am “greeted” by three new displays of the stars and bars.

Later, driving into town, I see three more.

I was raised in the Shenandoah Valley of western Virginia. I have been a college teacher in the Philadelphia suburbs for more than thirty years, but I still spend many weekends, and most of my semester breaks, in the South. I return, too, for several months each summer.

Writing now from this site, I am trying to puzzle through what has changed (or not), both in this rural southern county, and on my suburban northeast campus, since I first crossed the Mason-Dixon line, which I naively thought separated one from the other. In doing so, I find myself tracing a variety of ways in which institutionalizing diversity generates a backlash, as deliberate moves to create inclusive structures provoke pronounced displays of further exclusion—sometimes conscious, sometimes very much not so. Alexis de Tocqueville famously signaled the former, when he observed that “inequality is enshrined in mores as it disappears from laws.”Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. Henry Reeve (1831; repr. Gutenburg e-book, 2013). His focus, in 1835, was on the ways in which customs and conventions slow the pace of legal change, making abolition more difficult.

I focus here on a second, often unconscious, form of resistance that I’m calling “slipping”: an act of associative misspeaking that may be more iterative, more complicated—and potentially more hopeful—in its effects than the one Tocqueville described. I imagine the ways in which, if such slipping is endemic to learning structures, like my college, it might also be generative of their evolution. Such imaginings lead me to query a range of concepts often advanced in diversity work: those of “restoration” and “repair,” of offering “hospitality” to “strangers.” I ask also about the dangers of anonymity and privacy, about the counter-need and concomitant dangers of transparency and disclosure. Like other processes explored in this project, slipping is well characterized as a form of “ecological” thinking and acting: diverse, unruly, and fertile; conditional, uncertain, and incomplete—an unending process, very much dependent on the unexpected.

Asking in particular what it means to engage in such actions in the “contact zones”Mary Louise Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” Profession (1991): 33–40. that are intentional communities, I juxtapose the small town where I grew up with two institutions in the northeast: the small women’s college in the Philadelphia suburbs where I teach, and a nearby land-based village designed around the needs of adults with developmental disabilities. In fall 2014, some of my students got to know some of the residents here, by joining them for a week of work, and also by engaging in “the act of slow looking” needed to compose visual portraits of their lives.

The college and the village both seek “to sustain a community diverse in nature and democratic in practice,”Bryn Mawr College, “Mission” (1998). but are certainly challenged by the difficulties of doing so. At each—in the terms supplied by Sarah Ahmed, in her study of racism and diversity in institutional life—a “holding pattern” has become “intrinsic.”Sarah Ahmed, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 185–86. With the help of both Ahmed and Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose rising voice charts his “sense of the futility of individuals confronting the structure of white supremacy,” his “pessimism about what can be changed,” his doubt that “the future will be better than the past,” I acknowledge the strength of what he calls “the long arc of history.”Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “The Hard Truths of Ta-Nehisi Coates,” New York Magazine, July 12, 2015 (9:00 p.m.). But I testify also to the inevitability of its constant disruption.

It is precisely such unpredictability, and its surprising lessons, which catch me off-guard again and again; it is also such unpredictability that reminds me of the possibility of undirected change. In the village, the developmental disabilities of community members, and the lack of acquired “filters” that these entail, make slipping likely. Amid the rigorous academics at Bryn Mawr, slipping is just as inevitable, but often unnoticed; its potential has certainly been little unexplored.

Over ten years ago, I first heard the concept of “slipping” formulated, by a student, as a messy, slow—indeed, inevitable and unending—process. Emily Elstad, who studied “Big Books of American Literature”“Big Books of American Literature” (course offered at Bryn Mawr College, Spring 2003). with me in Spring 2003, wrote at the conclusion of that semester about the importance of attending to the gaps that open up when we misstep, misspeak. Emily’s essay, entitled “Slipping into Something More Comfortable,” anticipated much of the current discourse about embracing difference, acknowledging a “racial unconscious” that needs to be—indeed, cannot avoid being—brought into the open, in order to be addressed.Marguerite Rigoglioso, “Unconscious Racial Stereotypes Can Be Reversible,” Insights by Stanford Business (January 1, 2008). Beginning with an explanation offered by a local congressman, of a “slip” made by the mayor of Philadelphia, in addressing the NAACP—

The Brothers and Sisters are running this city! Don’t let nobody fool you: we are in charge of the city of Brotherly Love. We are in charge! We are in charge!

—John Street (Spring 2002)

You’re speaking your mind and sometimes you slip. We all slip.

—Lucien Blackwell, in response to Street’s comment

—Emily went on to draw on a range of classroom experiences, to argue that political correctness, or our fear of “mis”understanding, anticipates offenses that can

never be predicted, and that if we do not allow ourselves to “slip,” we cannot learn the truth about what we think or the truth about how others feel about what we think. “Slip” can mean “to slide or glide, esp. on a smooth or slippery surface; to lose one’s foothold” or “to break or escape—a person, the tongue, lips.” These definitions imply that what we bring to verbal “slippage” is involuntary, which suggests that in “slipping” somehow we access our unconscious, or what we “really mean.” Other definitions of “slip” include “to fall away from a standard; to lose one’s command of things,” and “to pass out of, escape from, the mind or memory.” These notions of “slip” posit a new state emerging from the act of slipping, a temporary loss of control that yields both a personal, subjective truth and a changed state that has moved away from “a standard” and into new thought and order. Instead of chastising people for ‘”slipping,” for describing the way in which they honestly think about the world, perhaps we should consider the meaning behind words spoken in moments of “slipping” and really think about how they speak to our world. Thinking metaphorically, sometimes only by slipping and falling to the floor do we notice that there is something down there that needs to be cleaned up.Emily Elstad, “Slipping into Something More Comfortable,” paper written for English 207: Big Books of American Literature, Bryn Mawr College, (Spring 2003).

At sites like Bryn Mawr, where many members have made intentional commitments to create an inclusive community, I’ve been learning how an unintentional “slip” might function, as Emily explains, to remind us that “there is something down there that needs to be cleaned up.” This making of messes, and then cleaning them up, never ends, but I also see how this process can function as an ongoing impetus not to settle in, a noting and questioning that can precipitate action and change.

Cleaning up is, also, not the only—sometimes not even the most useful—thing that can be done with a mess. What about exploring it? Painting with it? Surrounding it with silence? Meditating on it? Accepting it as the condition in which we live?

It is precisely the payoff, for institutional structures, of slippage, of the associative sort of thinking that isn’t seeking a particular end, and so tumbles into new—sometimes murky, sometimes illuminated—spaces, that I highlight here.