In this intolerable season, not only has the Confederate flag been on display on the Bryn Mawr campus, but non-indictments have been handed down in both Missouri and New York.Ryan Grim, Matt Sledge and Mariah Stewart, “From Daniel Pantaleo To Darren Wilson, Police Are Almost Never Indicted,” Huffington Post, December 3, 2014 (5:15 p.m.). College administrators begin to organize a Community Day of Learning, “designed to illuminate and consider the benefits and challenges of living and learning in a diverse community.”“Campus Comes Together for Community Day of Learning,” March 20, 2015 (1:06 p.m.). As I participate in the planning, I am feeling troubled by Sara Ahmed’s observations that “diversity management” might function as a way of “containing conflict or dissent,” “a discourse of benign variation” that “bypasses power as well as history.” I recognize how easily the language of diversity can be “mobilized as a defense of reputation,” “a means of maintaining privilege.” “The discourse of diversity,” Ahmed prods, “is one of respectable differences…used not only to displace attention from material inequalities but also to aestheticize equality.”Ahmed, On Being Included, 13, 151.

My immersion in the residue of history, of its continuing action in the dynamics of power, continues unabated as fall 2014 unfolds.

This semester, along with Kristin Lindgren, a colleague in Disability Studies, and Sara Bressi, who teaches in the Graduate School of Social Work and Social Research, I have co-designed a cluster of courses modeled on an intersectional approach to identity. Focusing, in particular, on those identity categories of “humans being” that may seem non-normative, we read, view, and create a range of representations, asking what stories we tell, and what images we construct, about ourselves and others—and how we might revise them. What are the possibilities, what are the limits, and what roles might others play in these re-imaginings?

A central event in this work is a co-curricular project conceptualized and led by artist and curator Riva Lehrer. During an extended stay at the nearby intentional community that includes adults with intellectual disabilities (called “villagers” by the other community members, who are known as “householders”), our students share in meals, participate in work assignments, and are welcomed into many other aspects of daily life. Among the group of villagers selected by the Volunteer Coordinator (based on their interest in the project and their capacity to pursue it), each one works closely with a college student to create a portrait that represents them both realistically and symbolically. Our students, in turn, complete drawings and portraits of their village partners. At semester’s end, the villagers visit Bryn Mawr, where they tour the campus, see the dorm rooms of their student partners, have lunch together, and exchange completed drawings and portraits.

At least that’s the plan.

The reality—of an active world, shaping and being shaped by active subjects, constrained by the limits of time and energy—turns out to be considerably more complicated.

Tobin Seibers describes disability as a “body of knowledge.”Tobin Siebers, “Returning the Social to the Social Model” (paper presented at the annual conference of the Society of Disability Studies, Minneapolis, MN, June 2014). His concept of the interactively-constructed self helps to highlight one very challenging dimension of our experiences at this dynamic farming, gardening, and handcrafting community, which is spread across hundreds of acres of farm, gardens, and woodlands. The bucolic site offers a local model for intentional, ecological living; it is filled with the pleasures of easy access to the natural world, and fueled by sustainable human actions, such as dairy farming, fruit and vegetable gardening, weaving, pottery-making, bread- and cookie-baking.

There is much here to enjoy and admire in this community; Riva compares, for instance, the sensory deprivation of being hospitalized with the multiple delights offered by the village.

Here “invisible people” are accepted as “social refugees,” made visible and useful. And yet, as one of the long-term householders also explained to us, “this is a community place, not a people place”; she means that individual empowerment is valued less than communal harmony—and such harmony comes at a number of costs, including those of diversity of race, class, and ability. The community does not offer a political or empowerment model of disability. It is insular, and strikes us, when we visit, as largely unaffected by time, modern technologies, and the demand of creating access for villagers whose families cannot afford the substantial fees for living here.

The three evocative photographs above were taken at the community by Rebecca,rebeccamec, “Fall Break Photos,” December 2, 2014 (19:19 p.m.), accessed July 19, 2015 one of the students in our course cluster.

Her role in capturing these images is a reminder that there is always someone behind the camera.

In mid-October, when we arrive at the village, one of our students is assigned to shadow a villager who tells her that she doesn’t like to be with people who look like her. Her saying so is a challenge to Riva’s vision of how we will “build the project around the concept of portraiture as relationship,” how “the act of slow looking fosters encounters that unfold differently from, or raise productive difficulties about, standard power relationships…of age, race, gender, and able-bodied and impaired.”Riva Lehrer, “Consent to Be Seen” (proposal for a panel on “The Ethics of Representation: How Context Matters,” to be presented at the Society of Disability Studies, Atlanta, GA, June 2015).

Many of the villagers lack the social filters which conventionally refuse to name, or look aside from, such differences. The villager who says she doesn’t like to be with people who look like our student, for instance, makes a very direct statement of personal preference and bias. In challenging our shared project of “slow looking,” the villager seriously queers some of the presumptions underlying it, forces my re-consideration of some of its standards. Is “seeing past stereotypes” our goal? Is forming friendships in such a short time, across such vast distances, a viable aspiration? Have we allowed enough time for this experience to unfold? If we haven’t, is it unethical? The finiteness of our end time feels powerful here.

All this is distressing to me and my co-teachers. We face Ellsworth’s unpredictable uptake. Brown’s unbinding.

In trying to make pedagogical sense of what happened here, I draw on an essay by Eli Clare, who visits my class on “Ecological Imaginings”“Ecological Imaginings” (course offered at Bryn Mawr College, Spring 2015). at Bryn Mawr the following semester. We read and discuss Eli’s “Meditations on Disabled Bodies, Natural Worlds, and a Politics of Cure,” which begins with a walk through a restored tall-grass prairie, and invites us to think from that place about the concept of “restoration,” of “undoing harm,” rebuilding a system that has been broken. It is an action that—while acknowledging that such a return will always be incomplete—is rooted in the belief that the original state was better than what is current.Eli Clare, “Meditations on Disabled Bodies, Natural Worlds, and a Politics of Cure,” 21.

Eli argues that this metaphor (like all metaphors) falls short, as a means of thinking through the concept of “cure,” if we imagine it as a mandate of return to a former, non-disabled state of the individual body. The desire for restoration is bound to loss, to yearning for what was thought to have been—but sometimes such restoration is not possible. In Eli’s story, as in many others, the original non-disabled body has never existed; such an account arises from imagining what the (normal, natural) body should be.

We discuss the limitations of this concept for those who are disabled, for those who are marginalized in other ways. Eli’s essay is a critique of the concept of a “restored” and “restorative” world, like that of the village community, and of the limitations placed on the possibilities of our engagement there. Eli says to us that “disabled bodies, like restored prairies, resist the impulse…toward monoculture.”Clare, “Meditations,” 19. In the creation of retreats for disabled bodies and minds, we need also find a way towards more varied acts of resistance to the monocultural.

For starters: markedly absent in my account so far has been an elaboration of the experience of the villager whose “unfiltered” dismissal can be heard as a conduit for prejudicial feeling. I don’t know much about the reach and limits of the villager’s mental capacities, except that she knows enough to say what she doesn’t like. The villager is paired with another of our students, Amelia, for the remainder of the week. Although the “success” of this substitution may well reflect and reproduce certain forms of privilege, the two of them are able to share a number of meaningful interactions over the course of the week.

The photos Amelia selects to figure her relationship with the villager are interactive: the two are seated close to one another, both smiling broadly. Amelia’s text—which is illustrated with colorful images of the natural world, of people and food—also witnesses to the pleasures of time “slowing down,” of “calm, comfortable” days when the only expectations are “being present and getting to know one another.”abradycole, “Zine Page,” December 18, 2014 (10:29 a.m.).

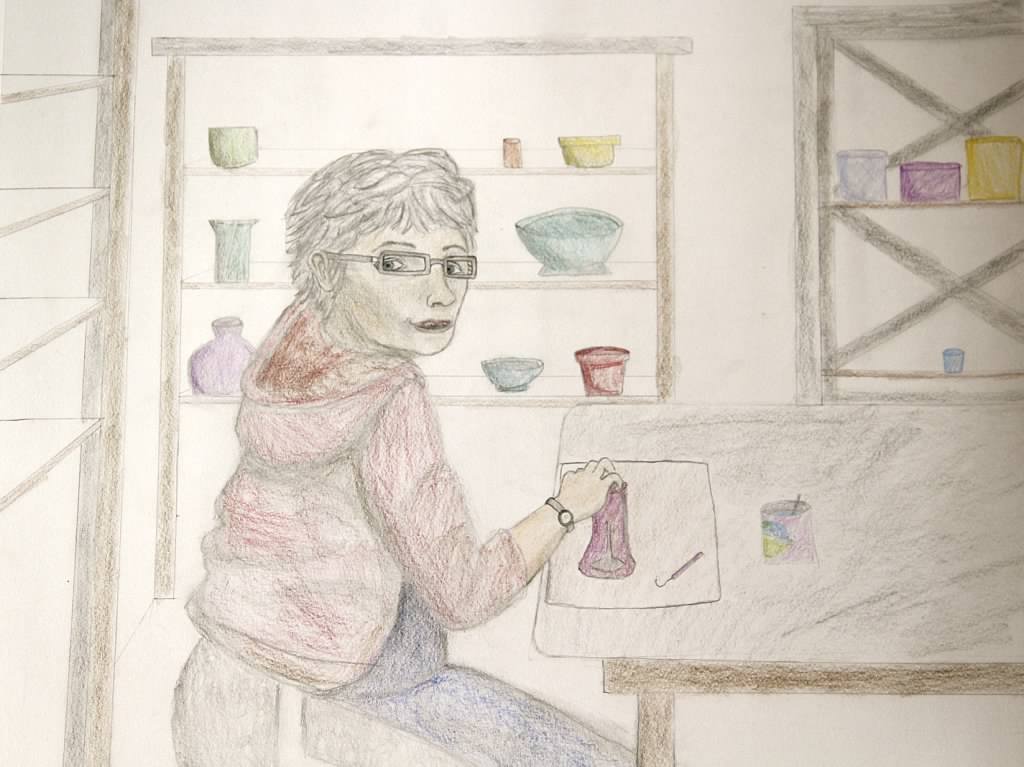

Amelia’s pastel drawing of the villager captures her at work in the pottery studio:abradycole, “Villager Portrait,” December 14, 2014 (11:25 p.m.). she has one hand on a vase she is making, while she looks up at the viewer, as if, in the midst of her work, she has been called out by another—called, perhaps, into relationship.

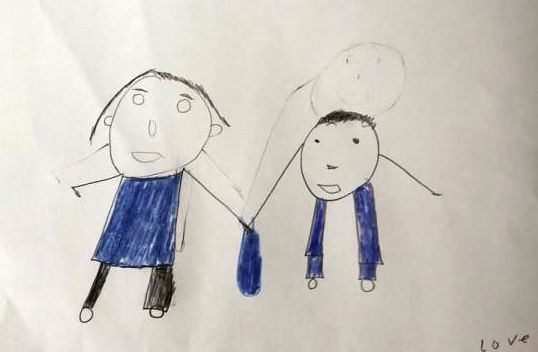

But perhaps the most profound image of such knowing is the doubled portrait of Amelia and herself that the villager creates.abradycole, “Drawing,” December 14, 2014 (11:26 p.m.). This pictures two figures, one in a dress, one in pants, who seem together to be carrying a bag; pants, dress, and bag are all colored the same shade of blue. Behind the shorter figure lies a ghost of an earlier sketch; the artist seems to have changed her mind about how tall she wants that figure to be….

I now imagine that ghostly figure as the villager’s first partner, who—due to a whole panoply of larger dynamics—is excluded from, and yet continues to haunt, this pair. The failure of that earlier relationship arises—not entirely deterministically, but not incidentally, either—from a range of conventional stereotypes, from historical and structural barriers to acknowledging one another, forming a working partnership, much less a friendship. In the village, which is intentionally shielded from the outside world, the student and the villager are unable to come to know one another as my co-teachers and I hoped they might. The villager is direct about her disinclination to work with the student—although there may be some complicated answers to the question of what it means for an adult with intellectual disabilities to make these statements.

Even as I bring into view her portrait and one of the images she created, the villager herself also remains something of a ghostly figure in my account. Silence surrounds my story of her, a silence that (as I explain more extensively in Chapter Four) both acknowledges my limits as a knower, and offers a space for questioning what it is I think I know about what happened here. Given the complexities of access in this process, how do I now understand our collective project of “ethical portraiture”? And (how) is it possible for me to provide an ethical account of what happened among us?

Eli Clare ends his own meditations on “disabled bodies and natural worlds” with a return to the tall-grass prairie, not “a retreat but the ground upon which we ask all these questions.”Clare, “Meditations,” 24. I, too, have a range of related questions about the complex valuing of difference as a form of both cultural and ecological diversity, and about how we might make such difference palpable and available.

Do my co-teachers and I need to return to the village, either with these students, or with another class, to keep on working through our partnership? Are different sorts of relationships possible among us?

Might a more active politics of difference enable us to move beyond our desires for restoration—of impairment, of a relationship, of a community, of a campus, of an eco-system?