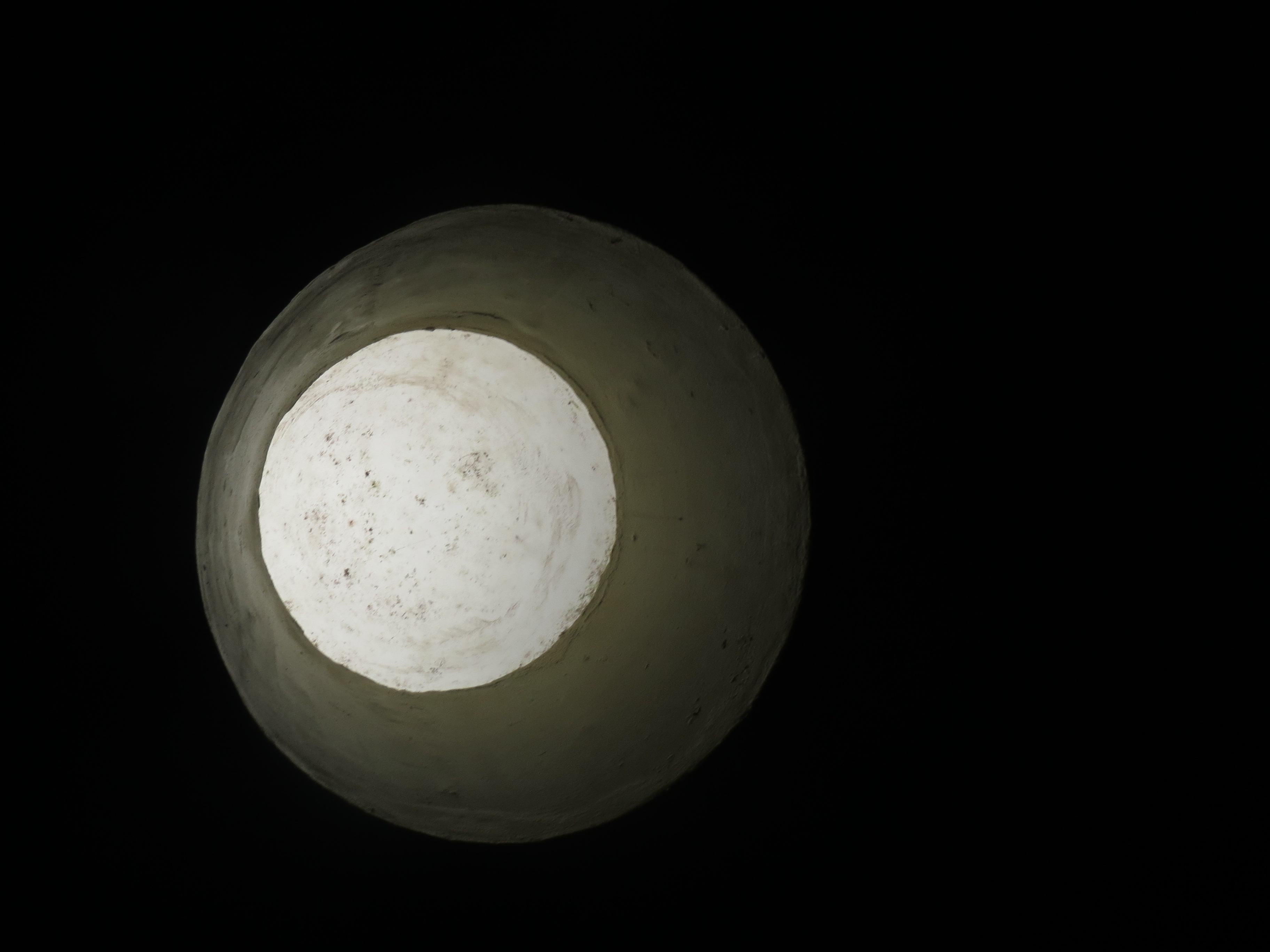

…the image…forces things to stop for a moment. It forces the reader to reinvent breathing so that the eyes can again focus… . I was attracted to images…with an incoherence…placed in the text where I thought silence was needed, but I wasn’t interested in making the silence feel empty or effortless the way a blank page would.

—Claudia Rankine, Bomb: Artists in Conversation

Taking the image also forces things to stop for a moment. One of the things I love about making photographs is the bubble of silence that surrounds me, as I pause to look around, note what is there, attempt to capture a scene, a pattern, a surprising juxtaposition.

I snap the image that prefaces this chapter in El Yunque National Forest, taking a break from the National Women’s Studies Association Conference, which was held in Puerto Rico, in November 2014.

I don’t begin writing the words that follow this photograph, however, until eight months later, when I return, a little stunned, from two more back-to-back academic conferences. Each session, at each conference, is held in a windowless room, chock filled with presentations, read at breakneck speed, with little time for uptake, for reflection, for talking back-and-with, for absorbing, for taking in.

At the end of each day, at each of these conferences, I query the colleagues who join me for drinks and dinner: Why are we reading, too much, too quickly, words that cannot be heard, understood, followed at such a pace? Why aren’t we making space for back-and-forthing, for co-creation and exploration? Attending to our needs for reflection, for apprehension, for uptake?

And why aren’t we leaving these closed, indoor spaces for more open, expansive, troubling ones? I take some time off to explore the intriguing, even startling, sites around us: the Society for Disability Studies conference is held just blocks from the astonishing Civil Rights Museum in Atlanta; I spend hours there one afternoon, absolutely gripped by the narrative, reliving the history—both what I know, and what I have not experienced. Tears running down my face, I find it hard to leave that space-and-time, to return to the conference up the hill—which is also contributing to a vibrant contemporary civil rights movement. Ten days later, the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment convenes in northwest Idaho, not far from both the Nez Perce Reservation and the original home of the Aryan Nations. Riding a bus into-and-through the reservation, guided by a Nez Perce elder, offers a different sort of interruption, not as immediately emotional for me, but one that also fills in, terribly, some of the silences of the history I have been taught. This makes it difficult for me, when we return to the conference venue, to sit still, in yet another closed room.

There is a lack of time in such settings; academics, engaged in pursuing-and-promoting our careers, need to carve out, of the little space available, efficient ways to demonstrate what we know to others in the field, who know other things.

And I do get very excited about this exchange of ideas, energized by quick-moving language.

But I want to talk here about our forgetting that silence, too, is resource. And source.

Spilling over with half-heard, half-caught ideas, frustrated with myself and my fellow-travelers for our failure to make time for silence in our gatherings, I here interrogate the “conference culture,” pause to question why this particular subset of the human species, that of the academic conference-goer—of which I am an ever-eager, ever-curious, card-carrying member—finds it so difficult to surround our speaking with stillness.

Like my colleagues, I have a lot to say.

Am not humble.

Cannot be quiet.

When George Prochnik traces the roots of our English term, these humbling dimensions, both of being silenced and choosing silence, are highlighted:

Among the word’s antecedents is the Gothic verb anasilan, a word that denotes the wind dying down, and the Latin desinere, a word meaning “stop.” Both of these etymologies suggest the way that silence is bound up with the idea of interrupted action. The pursuit of silence…generally begins with a surrender of the chase, the abandonment of efforts to impose our will and vision on the world…the pursuit of silence seems…to involve a step backward from the tussle of life… .“What’s silent is my protest against the way things are.”George Prochnik, In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise (New York: Doubleday, 2010), 12.

I’ve spent my life mostly pushing back against “the way things are,” and find it difficult to “surrender” to silence. It’s very hard for me to stop the search for explication, for revising the current explanation; I’m always trying to get it “less wrong,” always looking for the next (if never the last) word (and action). And yet (probably because this is so hard for me) I am also very much drawn to the practice of silence, and to the possibilities it opens up. That’s what I’ll be tracing in this chapter, as I excavate several layers beyond simple speechlessness, examining what silence might entail. Most obviously, space for reflection, for a fuller range of interpretation than quick speech might invite. Contrari-wise, help in acknowledging what cannot be said, even understood (so counter to the life of assured academic performance). Help in both re-thinking and re-working academic spaces to allow for these fuller, more uncertain slices of life. An invitation to look beyond the academic, even beyond the human, to the larger spaces we all occupy, to the unknown complexities that both inhabit and surround us, and the silences in which we might accede to that greater world.

I am guided in this direction, in part, by the masterful work of Eduardo Kohn, whose description of How Forests Think evokes a world of “other living selves—whether bacterial, floral, fungal, or animal.”Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 6. Kohn reads dreams, too, as “part of the empirical,” “a kind of real” that “grow out of and work on the world,” and argues that “learning to be attuned to their special logics and their fragile forms of efficacy helps reveal something about the world beyond the human.”Kohn, How Forests Think, 13. He also calls up the “pensée sauvage” of Claude Lévi-Strauss: “mind in its untamed state as distinct from mind cultivated or domesticated for the purpose of yielding a return.” And he mentions all the “‘mistaken’ utterances” that so fascinated Sigmund Freud, “the defective performance of certain purposive acts,” revealing “that which is ancillary to or beyond what is practical.” Kohn’s attention, via Lévi-Strauss and Freud, to thought “which resonates with and thereby explores its environment,” an insight that gestures “quite literally to an ‘ecology of mind,’” is key to my own.Kohn, How Forests Think, 176–77. But whereas Kohn’s focus is on “the multitude of semiotic life,” and how animals’ varied interpretations of the world contribute to “a single, open-ended story” in which we all partake, my own interests ultimately lie more in what cannot be signed, or signaled, in what may exceed representation.Kohn, How Forests Think, 49, 9.

Where silence falls.

…where is space for educators to be vulnerable about their not-knowing?

—a student’s comment

…silence…a terrifying moment for some teachers…something which instructors need to learn to “break”…it appears to be unproductive or damaging to self-development…numerous seminars about how to get students to talk, but none which deal with silence as a way to learn…implicitly understood in the humanities classroom to be a way to withhold information…an indicator of fear, boredom, resistance or ignorance.

—Julie Rak, “Do Witness: Don’t: A Woman’s Word and Trauma as Pedagogy”