When Mark Lord and I, who have been friends for many years, decide that we want to spend more time together, working and playing with the sorts of experiences and questions that matter most to us both—and that we hope might matter a lot to our students, beginning their first semester at Bryn Mawr—our new course on “Play in the City”“Play in the City,” Emily Balch Seminar, Bryn Mawr College, Fall 2013. gets its start. We know we can have fun co-designing a course around questions of how we construct, experience, and learn in the act of play; that we can use that concept to unsettle some of our students’ notions of what constitutes work, and education, and the work of education; and that it will bring us a particular pleasure to make the city of Philadelphia, eleven miles to the east of the College, our primary playground.

Our course will highlight play as a “way of knowing,” of being both present and distant, simultaneously connected and disconnected from what we might encounter. We intend to use play as “an instrument for staging various kinds of open-ended exploratory interactions…producing, questioning, and overturning different forms of life.”Paul B. Armstrong, “The Politics of Play: The Social Implications of Iser’s Aesthetic Theory,” New Literary History 31 (2000): 211–23. We hope that our students will discover, thereby, how intellectual work can be a form of play, play a form of intellectual work—and so unsettle conventional understandings of education as a process of completing tasks with known outcomes. We’re hoping, too, that they’ll grab on to the pleasures of working this-a-way, begin to shift their sense of how stakes can shift in such a game: perhaps in some ways lower, in others higher, than in assigned tasks?

Play is structured by the environment in which it occurs; we also believe that it has the potential for re-structuring that space, re-drawing the frame in which it is performed. Using Philadelphia as our primary “text,” a complex site open to observation, interpretation, and reinterpretation, gives us a space where we and our students can shape and re-shape their own identities, the way education is done, and perhaps what happens in the city as well.

So, from the get-go: this project is political. As Adeline Koh explains,

the ability to imagine, create, and live alternative realities…[is] the most political of acts…play reimagines the world…create[s] the potential to change it…“break[s] down our conventional, habit-dulled certainties about what the world is and has to be.”Adeline Koh, “The Political Power of Play,” Digital Pedagogy Lab, April 3, 2014.

For both Mark and me, the city has long functioned as such a site of intertwined personal and intellectual exploration, even (dare I say?) liberation. As he (re)tells the story, I first found my way to Philadelphia from the rural South, “looking to lose something, a set of familiar associations and ties, to gain anonymity and a capacity to play,” while he came in from closer by, “was feeling the vapidity of my suburban life without associations or meaningful connections and came seeking events/scenes to tie myself to.” Our points of departure differ, but each of us finds an alternative in Philadelphia, “the sense of excitement that comes from having been excused from the unitary identity you are cast into in your town/family/landscape of origin.”mlord, “poor b.b. (plus),” May 6, 2013 (11:21 a.m.).

Excused, by the complexities of the city, from our unitary identities.

In arranging for our students to spend time exploring Philadelphia, we are also seeking ways for them to expand their own sense of identity. We think that, through their connections to us, to one another, and to the city, they might learn ways of nourishing themselves, socially, emotionally, intellectually, culturally, spiritually, politically. Some of them will already be intrepid social and intellectual adventurers. We’re hoping that—if we can extend the web upholding them beyond our suburban campus, if they can come to recognize that their resources encompass the larger metropolitan area—all of them might become more resilient in facing the pleasures and challenges of life in college and thereafter.

In “Urban Friction,” an essay we will use in the course, Jonah Lehrer shows us some ways in which the city can exacerbate the sort of creative tensions we are seeking to pose for our students. Lehrer notes that “knowledge spillovers” happen in densely populated spaces, where the “sheer disorder of the metropolis” forces mingling across “social distances” and a “range of worldviews.” Otherwise, he observes, everyone will “naturally self-segregate, choosing to spend time with people who are just like ourselves. (Sociologists refer to this failing as the self-similarity principle).”Jonah Lehrer, “Urban Friction,” in Imagine: How Creativity Works (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2012), 182–83.

Lehrer vividly describes the entry of suburbanites into an expansive, diverse urban space, where they experience “‘informational entropy’ (the presence of disorder—think of a crowded sidewalk).” The “us” and “we” for whom he speaks here are clearly not urban dwellers, but those newly encountering the city: “the metropolis…constantly introduces us to the unexpected and curious….knowledge leaks from everywhere…we must engage with strangers and strange ideas…”Lehrer, “Urban Friction,” 202.

Authorizing our students to attend to “leakage” and encounter “strangeness” indicates our plan to use play pedagogically. This is not exactly the same as playing, and hints at ways that the outcomes of our pedagogy may exceed our intentions… .

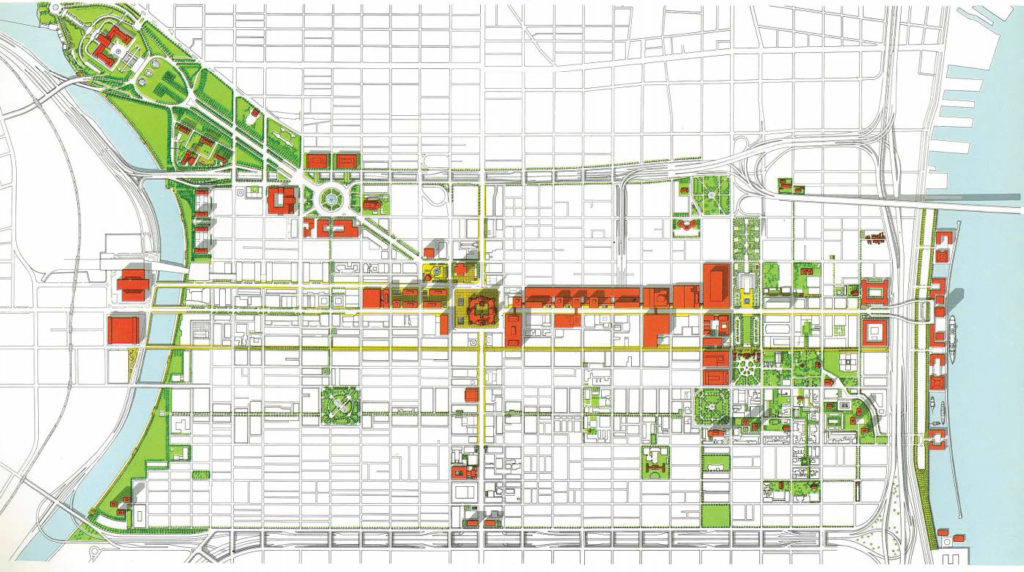

Lehrer celebrates such “spontaneous mixing, all those unpredictable encounters,” as keeping the city “alive.”Lehrer, “Urban Friction,” 211. A similar interruption of design is also well demonstrated in Philadelphia’s city plan, which Mark glosses this way:

City Hall itself is a 19th century “play” on the Original Grid, covering over the Center Square. (That a part of this square is currently excavated delights me btw.) Even the grid is a slightly playful attempt to insert civic meaning between the two rivers, which are themselves an ecocentric “grid” of an irregular system. All the civic attempts to organize and regulate meaning in the city are subverted daily by the needs/desires/habits of actual people. And part of the majesty of the cityspace is its absolute resistance to efforts to fix its meaning—but also its reluctance to turn into complete chaos.mlord, “not changing mine,” May 8, 2013 (6:19 a.m.).

The multiple ways in which Philadelphia resists all “efforts to fix its meaning” makes designing a course in the city itself an endless exercise in meaningful play. Mark and I trade articles, books, websites, films. He dares me to make our conversations—and all the planning they entail—public. I do. He supplements this linear on-line record of our thinking-in-tandem“Planning to Play,” Bryn Mawr College, May 10, 2013–August 28, 2013. with a more tactile, spatialized process, using variously colored post-it notes to make visual the different dimensions of our emerging class. We take jaunts, together and apart, to various sites, meet up in city parks to brainstorm next steps, plot multiple trips for our students. Some of them will enter already savvy about how to take the commuter train, the high-speed line, the trolley; others will need to be guided by us into increased independence, as they travel first in small groups, then pairs, finally alone…

We design a course demonstrating our belief that classrooms and other conventional learning places are arbitrarily bounded containers that can overflow, short-circuit—and be re-ignited by playing and learning “outside.” We select Serendip Studio, “a digital ecosystem, fueled by serendipity,” as our “public playground,”Serendip Studio, Bryn Mawr College, 1994–2017. an on-line site where students will post, and we will respond to, all their writing. We order tickets to 17 Border Crossings, a series of short plays by Thaddeus Phillips, each examining the complicated process of stepping from one country to another. Thaddeus Phillips, 17 Border Crossings, FringeArts, November 13–17, 2013. We will also draw our students’ attention to the Jewish eruv, intentional spaces now demarcated by clear, nylon fishing wire, strung between existing landmarks in Philadelphia.Joseph Brin, “Borders And Boundaries, Invisible To Most,” Hidden City Philadelphia, October 23, 2013.

In making such choices, we are refusing the boundedness of campus and city, “inside” and “out.” That refusal is a playful political intervention in the conventional maintenance of borders. We will repeatedly cross such boundaries with our students, together tracing out possible trajectories of play and threat, risk and refusal, as we “test the possibilities of contact” in “an emergent field of uncertainties.”Deborah Bird Rose et al., “Ravens at Play,” Cultural Studies Review 17, no. 2 (September 2011): 340. Recognizing the boundaries of inside and out, acknowledging ways that play is often discouraged in classrooms, we look not only to go out but also to bring play into our classrooms.

Even before our students arrive, multiple cracks appear in our plan. (How could they not, given the unpredictable outcomes of playful exchange?) Throughout the summer, we negotiate with various administrators, trying to cobble together enough money to pay for each of our students to take the train into the city seven times, and to pay, as well, for their explorations there. Although Bryn Mawr has long advertised its proximity to the “expansive, global, civic community” of Philadelphia, it has not yet put many resources into funding access to Center City. We understand something about the economic challenges of running a small liberal arts college, but also find ourselves provoked by this particular instantiation: more attention is given to marketing our access to the city than to making it easy for our students to get there.

When our good friend and colleague Alice Lesnick explicitly re-frames that tension, we see how much she’s raised the stakes of our game. During our summer of planning, Alice suggests that we think more carefully about whether our focus on “play” in the city might run the danger of exoticizing the space, making it seem as though we’re framing it as a playground for those of us who will be coming in from our suburban college.alesnick, “play/ground,” May 6, 2013 (5:56 a.m.). Alice asks, “Who is the ‘We’?”:

This question seems to be flickering around a good deal of this thread. When your classes go “into” the city—what “we” will be so constituted? Whose city? When extrinsic and when intrinsic? What “we” pees on trees? How much of being within a “we” is about policing, or defining, boundaries? I’ve been remembering the old Take Back the Night times when I was in high school. Was that play? I remember feeling loose of some fear I knew when a girl in Philadelphia. Are today’s Slut Walks play? Or, like Occupy, are they leveraging play as discourse?alesnick, “Who Is the We?” May 10, 2013 (10:50 a.m.).

Coming to college may require our students to take up the complexities of its location.

The politics of difference are now in play.