In early September, we welcome twenty-seven first-semester students, and so begin to enlarge the scope of our game. The arc of the semester plays out largely in the way we imagine—which means that, like all courses (but perhaps more so?) it is full of the unexpected. The students are (mostly) engaged, (mostly) delighted by our frequent jaunts into the city, (mostly) willing to explore both the experiential and theoretical dimensions of our work. They are simultaneously resistant to all of the above, especially as they begin to discover how political it can be to “play.”

Early on, we ask them to use Robin Henig’s “Taking Play Seriously” to reflect on their own childhood experiences of play, and then to consider the relationship between such experiences and their current intellectual life. In response to Henig’s argument that “imaginative play…creates a person…who believes in possibilities…in acting out one’s own capacity for the future,” some of our students offer poignant accounts of being denied this “more diverse and responsive behavioral repertory.”Robin Henig, “Taking Play Seriously,” New York Times, February 17, 2008. Cathy Zhou, who has come to Bryn Mawr from Chengdu, China, writes:

The essay of Henig totally recalled my memory of family times, when my father always complains how technologies have been ruining my childhood: I have never climbed trees or catched an insect in my childhood…But there was little time for playing since I was attending preschool classes and take piano, drawing, handwriting, taekwondo at the same time. [My parents] don’t want me to be left behind by other kids, and arranged a busy schedule for me.Cathy Zhou, “Personal Reflections,” September 11, 2013 (1:20 p.m.).

Our students are even more tightly scheduled now, as they figure out how to juggle their new obligations at Bryn Mawr; our invitation to embrace play as a version of intellectual work provokes some grumbling about giving “carefully hoarded time for trips…between working on Saturdays, rehearsing for a play, and finishing homework.”Claire Romaine, “Stubborn Writer,” December 19, 2013 (9:24 p.m.). The students’ reticence is a reminder of the pressures at an academic institution where playful exploration is elusive and seems pitted against the call to accomplish, to own, to earn one’s way through, to support others.

Acknowledging these constraints, we still insist that our students “unbind” from the classroom, go out from the line of seats or the circle of chairs that have (mostly) circumscribed their learning, and begin to engage the world more directly, with less teacherly mediation—and then reflect on what happens. Like Deborah Bird Rose and her co-authors in “Ravens at Play” (a lovely, deep piece on multispecies possibilities for social interaction), we have only inklings, setting out, of the diverse opportunities that may be “both opened up and foreclosed by any kind of play we might choose or be able to engage in with others.”Rose et al., “Ravens at Play,” 341. We saunter out for adventure, planning to make ourselves “at home” in the city. The hard questions of cultural crossing—of access and belonging, appropriation and trespass, the politics of “playing”—are yet to come.

On our first trip, we participate in one of the productions of the Fringe Arts Festival. Headphones on, we sit side-by-side at tables in the reading room of The Free Library of Philadelphia, following cues—some written, some whispered—that guide us through a pile of books in front of us. We are each performer and spectator in The Quiet Volume, a self-generated performance that engages us in a “drama of turning pages, pointing fingers and eerily drifting thoughts,” and so invites us to “listen to what’s going on in our heads when we read.”“The Quiet Volume,” FringeArts, August 2, 2013.

Quickly noticing that a number of our companions at the library tables are not listening to instructions through headphones, our students realize that they are participating in much larger, explicitly inequitable theater, both in the library and on the streets. They began to notice some “cracks” in the classic urban studies texts we’ve assigned them; the theories of Lewis Mumford, George Simmel, Sharon ZukinLewis Mumford, “What Is a City?” Architectural Record (1937); George Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1950); “Sharon Zukin, The Cultures of Cities (1995)”, urbanculturalstudies, May 21, 2012. seem distant from their own experiences, romantic versions of what they are encountering. Another student from China, writing under the name “Everglade,” reports feeling

dumbfounded…by so many homeless people in the brightest and most fancy part of the city…here they have the freedom to sleep in the perfect Logan Square or under the statue of a war hero, skateboard in Love Square, and look so vibrant under the warm Saturday sun. Just a few steps away, in the small streets straying from the broad and gorgeous Benjamin Franklin Pkwy, their scrawls are everywhere, and when they are merely standing there talking I can sense their movement like dancing. This is what Sharon Zukin says, “a kind of low-down but truer sense of where the self can develop”.

After wandering for a while, I went in the Free Library—also the territory of the homeless. I sat among them and started to enjoy the Quiet Volume…they were talking and smiling. They seemed warm, too, in their hoodies and caps.

It seemed that I was so interested in the homeless people and considered them artistic hermits in the city. But then I came face to face to one. It was a total shock, when I was sitting on the terrace looking for my water kettle in my bag and a straggly old man just walked towards me and started murmuring. Startled, I said I don’t understand English and left. Well I wasn’t lying, because I didn’t understand a single word he said. But as I walked away I heard a sentence that I could catch, “I just wanna give you a compliment!” This should be a great example of the “serendipity” that I’ve long craved, but what did I do? I ran away in panic, maybe because the stereotypical fear of the homeless people. I felt regretful afterward—I should’ve chatted with him and explored lots of things that’d surprise me….

So I’m not as open-minded as I thought. I should, and I will, open up more to different people and ideas, to surprise and excitement, to serendipity.Everglade, “Open to Serendipity,” September 16, 2013 (12:01 p.m.).

Throughout this book, we celebrate the serendipity of surprise, advocate for openness to unexpected possibility. We also spend some time on the possible downside of such experiences: something unwelcome could happen, the students may not feel able to say “no” to what they encounter. We don’t attend much, however, to the jolt of awareness of our own limitations, the disappointment in ourselves for not being able to seize a new opportunity. Everglade names such experiences here: how her trip begins playfully, becomes threatening; the value and also the risk of her coming to the city, the sense of exposure this entails.

Everglade reports panic, fear, and disappointment; a classmate describes another unsettling encounter in Philadelphia that leaves her feeling hopeless. Agatha Basia, who has lived in a number of different cities in Africa, Europe, and the U.S., begins her account by challenging Mumford’s observation that “The city…is art; the city…is the theater”:

Is that the responsible thing to do? Make art and poetry of human struggle?

I walk downstairs to the washroom in the Free Library in Philadelphia, because I still have a few minutes before the fringe festival performance begins…

I go into the third stall. There is no latch on the door; instead,

the hole where the latch should have been is stuffed with a thick wad of toilet paper. It holds the door closed so I don’t mind.

There is a woman in the stall to my left. She is sobbing. I don’t know if she is standing or sitting, but she is shuffling her feet nervously. And she is sobbing, mumbling in a panicky voice. I can’t understand everything she says because it doesn’t seem to all be in English. But I can hear her words —between sharp, ragged breaths—that nobody knows, don’t nobody know. Nobody.

And her voice sounds like pain and fear. Airy, high and small. Choking and weary and trembling. Small.

And I can’t say anything. I can’t ask her what is wrong or if there is any way I can help. There is much more than just the wall of a bathroom stall between us. I leave my stall, walk to the sinks and wash my hands. The woman is still in the stall, crying, speaking to herself as I dry my hands and walk outside. And that is that. I remain simply with the voice and tearful, frightened words of a faceless woman in a stall next to mine… .Agatha Basia, “Spectacle,” September 16, 2013 (12:13 a.m.).

Like Everglade, unable to make contact with someone who is unsheltered, Agatha places her sense of individual hopelessness in a larger context, believing that multiple social structures—“much more than just the wall of a bathroom stall”—keep her from speaking to her neighbor. On our first trip to the city, “play” has quickly become unsteady, destabilizing, bringing students face to face with social inequities, leaving some of them worried and troubled. We have moved rapidly from the celebration of undirected play, with which our course began, into a range of more complex and subversive forms, both experiential and theoretical. Henig’s claims that “the aim is play itself”—with “unproductivity” its essential aspect, “open actions,” “occasions of pure waste”Henig, “Taking Play Seriously.”—are replaced now by challenging encounters with other people.

We begin to ask if we might use play to unsettle such situations, “to defy orthodoxy and top-down power, and envision a new society.”Pat Kane, “Protean Activism: The Constitutive Politics of Play,” The Play Ethic, July 12, 2009. We read Mary Flanagan’s assertion that “play is never innocent,” follow her accounts of various forms of “critical play,” challenges to the status quo that are intended to shift paradigms, the boundaries of what is permissible.Mary Flanagan, Critical Play: Radical Game Design (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009), 1–15. Slowly, as the students research a wide range of artists who “play critically,” spend some time themselves alone in silence—first in a cell in Eastern State Penitentiary, next with a work of art they choose at The Barnes Foundation—then map their own trips into the city, exploring it in accord with their own desires and designs, they begin to recognize ways in which being playful in undirected but curious and thoughtful ways might guide them into larger questions, and also into larger meanings.

We now hear named some of the risks of what we are up to. We learn about Jeremy Betham’s concept of “deep play,” reprised first by Clifford Geertz,Clifford Geertz, “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” in The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973). then Diane Ackerman: “any activity in which ‘the stakes are so high that…it is irrational for anyone to engage in it at all, since the marginal utility of what you stand to win is grossly outweighed by the disutility of what you stand to lose.’ ”Diane Ackerman, “Chapter One,” Deep Play (New York: Random House, 1999).

As we begin sharing examples, comparing stories about when we each might have experienced deep play, some students struggle with understanding the role of such “irrational” activity, how appropriate high risk might be in the classroom. I describe teaching as my own preferred form of deep play. A student realizes that she has had the experience of playing deeply at another academic task: Yancy, who has also come to Bryn Mawr from China, and who finds it difficult to speak in class, articulates her own experiences

in the library on Friday night, with my computer. Silence is everywhere, and there is no one else in my eyes. Friday night, the wonderful night, because others take part in parties or play in their room, the library seems so spacious for me. I sip some hot milk and stare at my screen, there are massive codes here…my spirit is concentrated in those codes…I do not care how much time I will spend in this work, and how difficult the work is. Time is passing, the milk is cooler. I just sit here silently, tapping on the keyboard… . Those codes are…regular, beautiful and creative. The code is a new language used by people to express the beauty of the world and I just need to use a simple media to turn the codes into pictures to understand the writers’ ideas. Isn’t it amazing and fantastic?

I know when I am writing codes, I experience the deep play…based on mental happiness…special because of its meaning and privacy… . I write the codes like the pilgrim looks for Mekka. We both need something to find the meaning of our lives.Yancy, “Deep Play,” November 18, 2013 (12:04 a.m.).

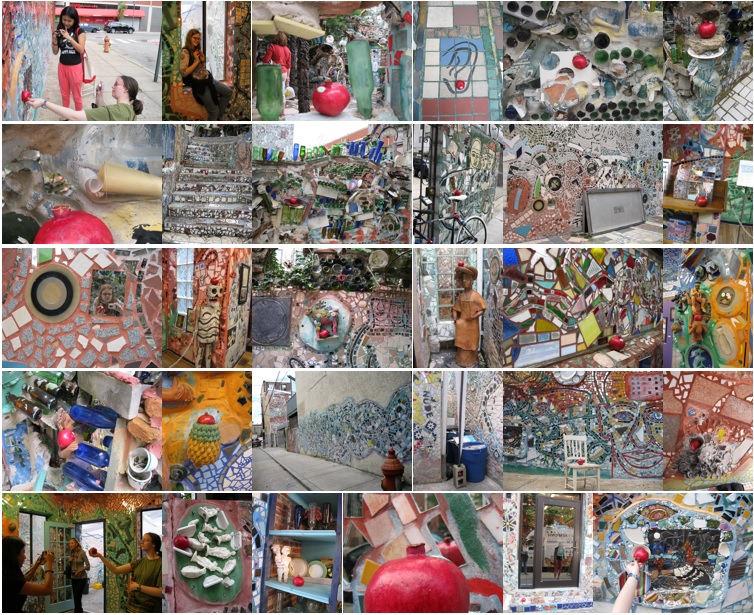

Slowly, other students begin to engage in writing that is deeply playful. Their work becomes more experimental. Mark and I create “text renderings” of their essays (noting words, phrases, sentences that have “heat,” or “energy”); then they do this for one another. These risky attempts put them into new relation with one another. They make (mostly verbal) mosaics out of Terry Tempest Williams’ fragmented text, Finding Beauty in a Broken World;Terry Tempest Williams, Finding Beauty in a Broken World (New York: Vintage, 2009). then mosaics—(mostly) visual, though one takes the form of a sound trackAgatha Slobada, “Julia of Eyes,” Soundcloud.—to represent their spirited excursions to Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens, then tracking down the street mosaics of Isaiah Zagar.

The students come to understand mosaic as a critical practice, a mode of playing with different juxtapositions of both visual and verbal material.

They learn to play with point of view, sharpening and shifting their “lenses,” making them “distinctive,” then “collective.”

They take more risks in their writing, finding doorways and openings into play. One student says that

this course gave me…the decision to write essays about questions that I don’t have the answer to. This is terrifying… . But, more recently…I feel quite fearless…No reservations. No worrying about what Anne will say or what my classmates will say or (oh my!) what my future employers might say… . After I take away the intimidation and the roadblocks, I just go. And it feels like joy. Really, I feel quite joyous writing this right now…tomahawk, “Ruminations on the Class,” December 20, 2013 (2:38 a.m.).

Another student, Paola Bernal, finds that writing “without filters”pbernal, “Learning to Write Without Filters,” December 18, 2013 (3:20 p.m.). leads her into sharp political critique, an awareness of how cultural boundaries are policed. Paola appreciates

that museums ultimately mean well and all they want is to preserve these collections for more and more people to have a chance to enjoy as well. But, for my mother and many other underprivileged people who didn’t have the opportunity of receiving an education or the chance to pursue higher education, art museums have become an unwelcoming place… . Art Museums are…feared.pbernal, “Art Museums: Do they enlighten or isolate people?” December 10, 2013 (2:48 a.m.).

In Paola’s experience, The Barnes Foundation

is quiet and rigid; I’m walking in an architect’s wet dream. This isn’t a place for the people to learn about art, it’s a showcase for the pompous and wealthy to wander and critique at their leisure. I feel like I’m invading someone’s space, someone’s dream. It doesn’t feel right, I don’t feel welcomed… .pbernal, “Garden of Eden,” November 25, 2013 (12:19 a.m.).

Paola and her classmates begin to ask hard questions about intellectual property: should art belong to particular individuals, or be accessible to all? What about forgery, understood as admiration and celebration? What about re-mixing?tomahawk, “The Barnes Foundation and Intellectual Property,” December 1, 2013 (10:33 p.m). On their last foray into Philadelphia, when each student is traveling alone (as it turns out, in the midst of a snowstorm), they are not just playing in but with the city, tracing musical clefs in the snow, making their marks on a landscape where, as Tim Edensor and his colleagues observe, “play may best be conceptualized as always potentially emergent, with the potential to shift the actuality of the moment in unforeseen ways, generating encounters which could always have been otherwise.” Tim Edensor et al., “Playing in Industrial Ruins: Interrogating Teleological Understandings of Play in Spaces of Material Alterity and Low Surveillance,” in Urban Wildscapes, eds. Anna Jorgensen and Richard Keenan (New York: Routledge, 2011), 65–79.

Still emerging for our students, as this semester ends, are the problematics our friend Alice named the summer before: “Who is the ‘We’?” “Whose” is the city? Sited differently, Alice’s questions echo those Lisa Delpit asked twenty years ago, in Other People’s Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom. Delpit argued that process writing approaches fail to provide low-income students with access to the “codes of power” of “Standard” English:

There is a political power game that is…being played, and if they want to be in on that game there are certain games that they too must play… . Only after acknowledging the inequity of the system can the teacher’s stance then be “Let me show you how to cheat!”Lisa Delpit, Other People’s Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom (1995; rpt. The New Press, New York: 2006), 39–40, 165.

In Delpit’s formulation, play is very serious, its possibilities circumscribed by variable access to power. Our course has been highlighting similar questions: What enables play, we ask again and again—and what prevents it? Who gets to name the stakes at play? Who gets to play in the city, as in the classroom? How much security do “we” need to have, before we are “free” to take the risks of playing freely? Is this never possible? Does play always take place within restraints? And also always entail unpredictable consequences?

Like the unexpected interactions that Deborah Bird Rose, Stuart Cooke, and Thom Van Dooren trace with coyotes, then ravens, our own pedagogical play enters into and sets in motion a precarious, shifting landscape in which we encounter not only others but also ourselves as “strange strangers,” whose gestures puzzle and elude us, eliciting responses we didn’t know we had, restraints we weren’t aware of, hadn’t recognized as necessary. Rose, Cooke, and Van Dooren say they are “willing to test the possibilities of contact, but…at the same time suspicious of where our attention might lead.” Reflecting on the consequences, for other species, of playing with humans, Rose and her colleagues ask,

Was the best gift we could offer actually a restraint—that we would withhold ourselves…our play? We couldn’t play in good faith, because while the game was a transient moment for us, it was a trajectory toward death for [them]… . What we might become in the contact zone was thus constrained… .Rose et al., “Ravens at Play,” 341.

We end our semester with many related questions about our own attempts to “play in the city”: Has our concept of a playground been based on a presumption of naïve users? How transient have our interactions really been? What have been the consequences of our play for those who live in Philadelphia, or for others who may visit there? Should we have played more expansively—tried harder to make contact—or been more constrained? How might we have acted differently, more thoughtfully, more responsibly?

Agatha reprises the time we have spent together by saying that she still feels uncomfortable “about the concept of ‘playing in the city,’ as if the city were a playground. It’s not easy for me to ignore all the hardships and political issues and absurd human drama that is played out in a city… .”Agatha Basia, “Decided. Dreams Collection.” December 17, 2013 (8:57 p.m.).

The experiences of other students lead them, like Agatha, to develop critical perspectives on play, identity, education, the city-suburban divide, social inequities…for these students, now, the “usual conventions of property, commodity and value” no longer pertain. Recognizing play in the city as a space of “productive, generative practices,” “potentially transformative” and “subversive of power,” they offer a strong articulation of what going “outside the classroom” might mean.Edensor et al., “Industrial Ruins,” 65–79. They query the sort of education offered on campus, and invite larger questions about what is “proper” both here and elsewhere.

Mark and I are left, too, with questions about the relationship between risk, privilege, and play. How might locating play outside classrooms mitigate or invite play inside them? At what times and in what places might play be destructive rather than beneficial?

Cathy Zhou

Cathy Zhou Everglade

Everglade Agatha Basia

Agatha Basia Yancy

Yancy tomahawk

tomahawk pbernal

pbernal